Assistant IA DPO

DPO, optimisez votre temps de travail grâce à notre assistant IA

⏳ Gagnez jusqu’à 2H par jour

💰 100% Gratuit

Ce qui vous demandait des heures ne prend plus que quelques minutes.

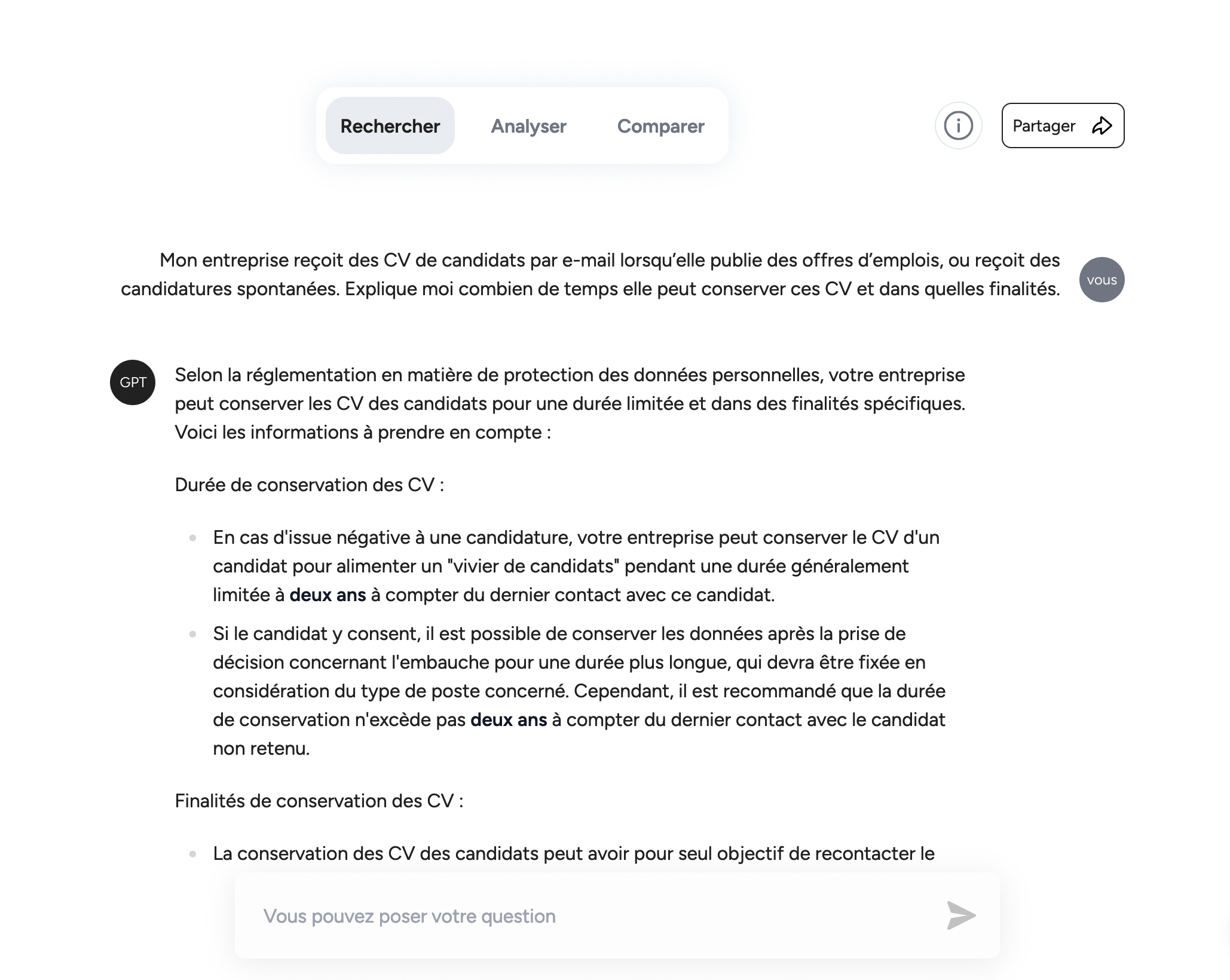

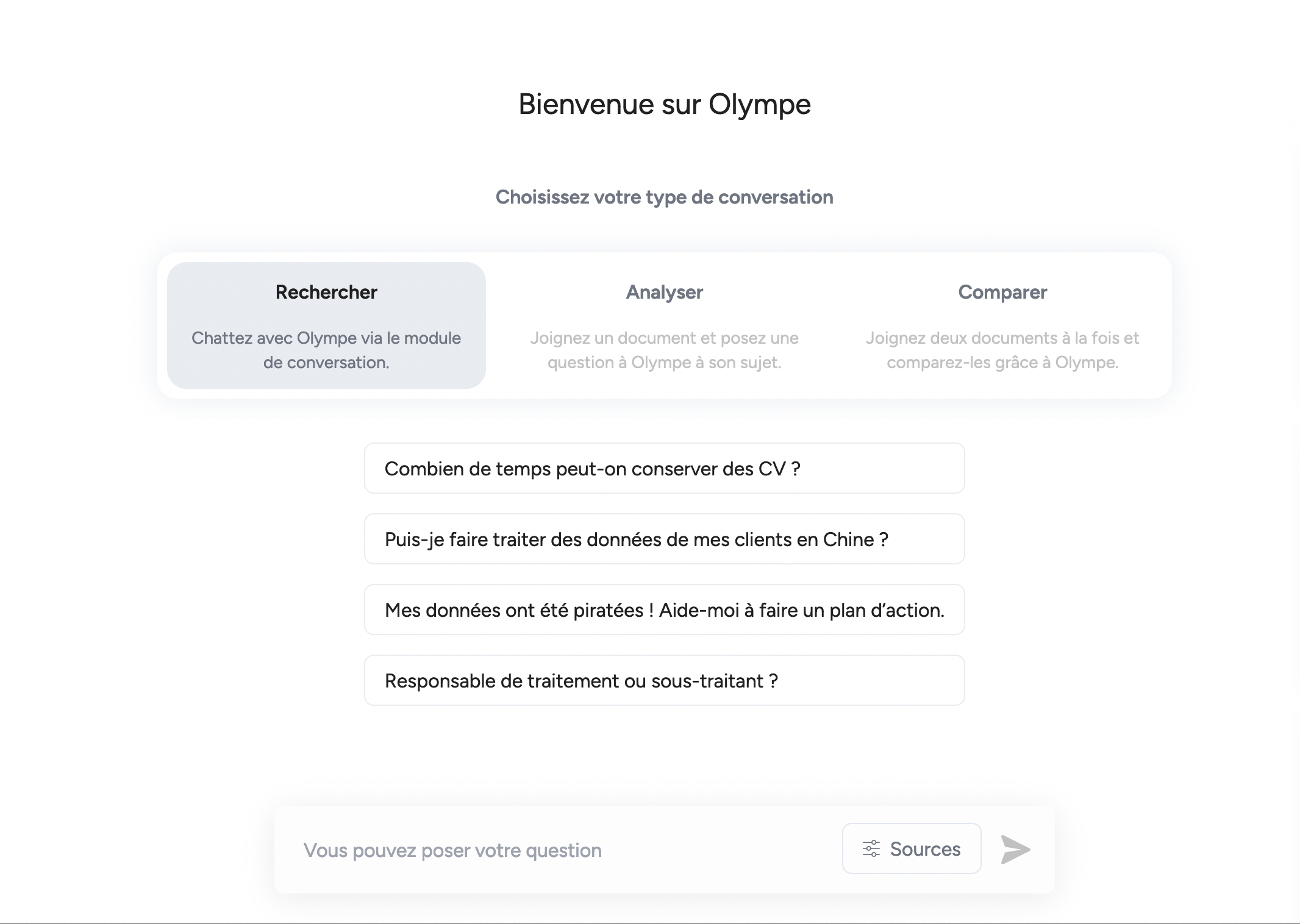

Gagnez 80 % du temps de votre recherche juridique

Olympe propose un moteur de recherche qui vous permet de trouver l’information juridique et technique pertinente en quelques secondes.

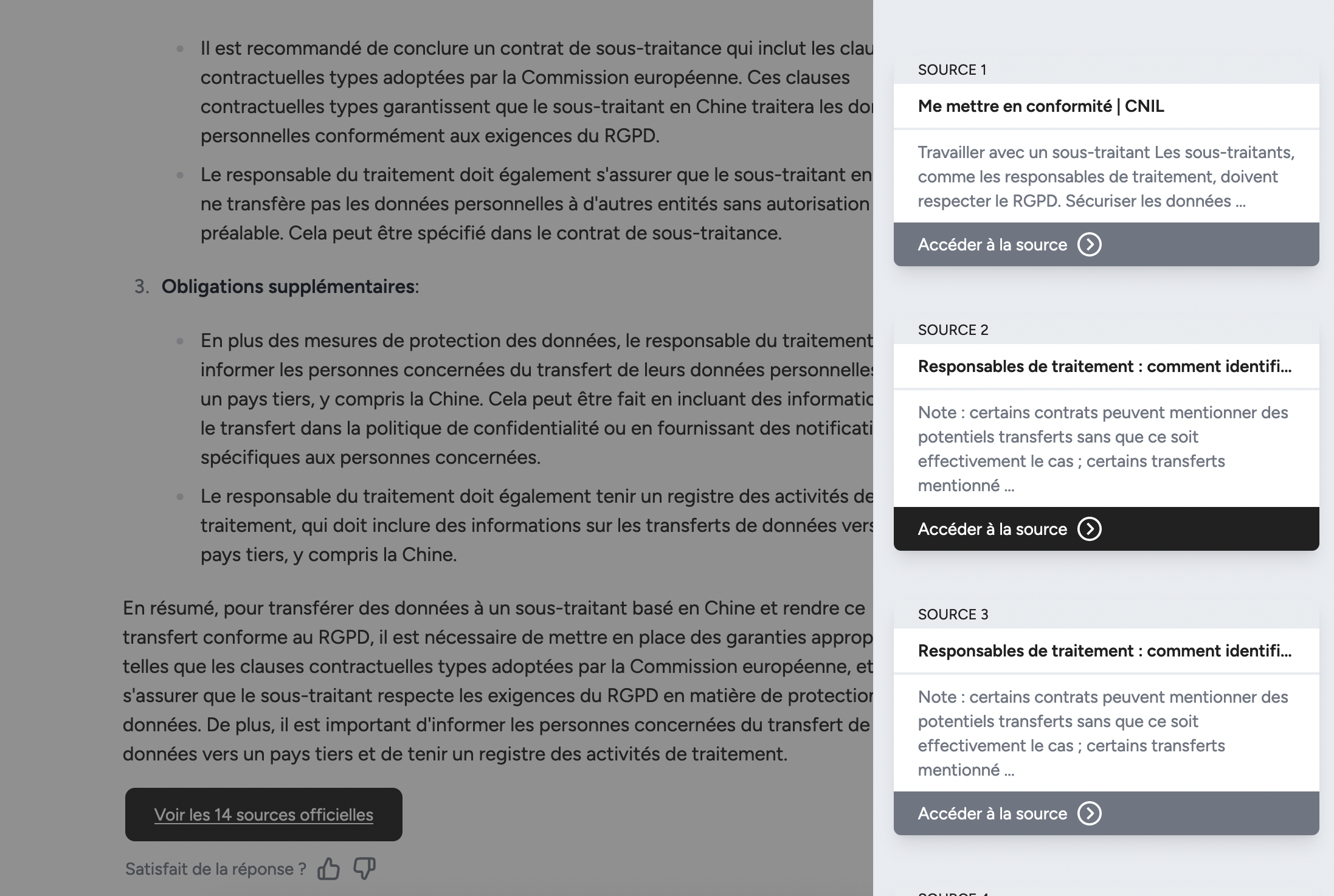

Appuyez vos réponses grâce à des sources fiables

Olympe vous répond en citant ses sources et vous permet de rédiger des réponses pertinentes rapidement.

Accédez aux sources et consultez-les en un clic.

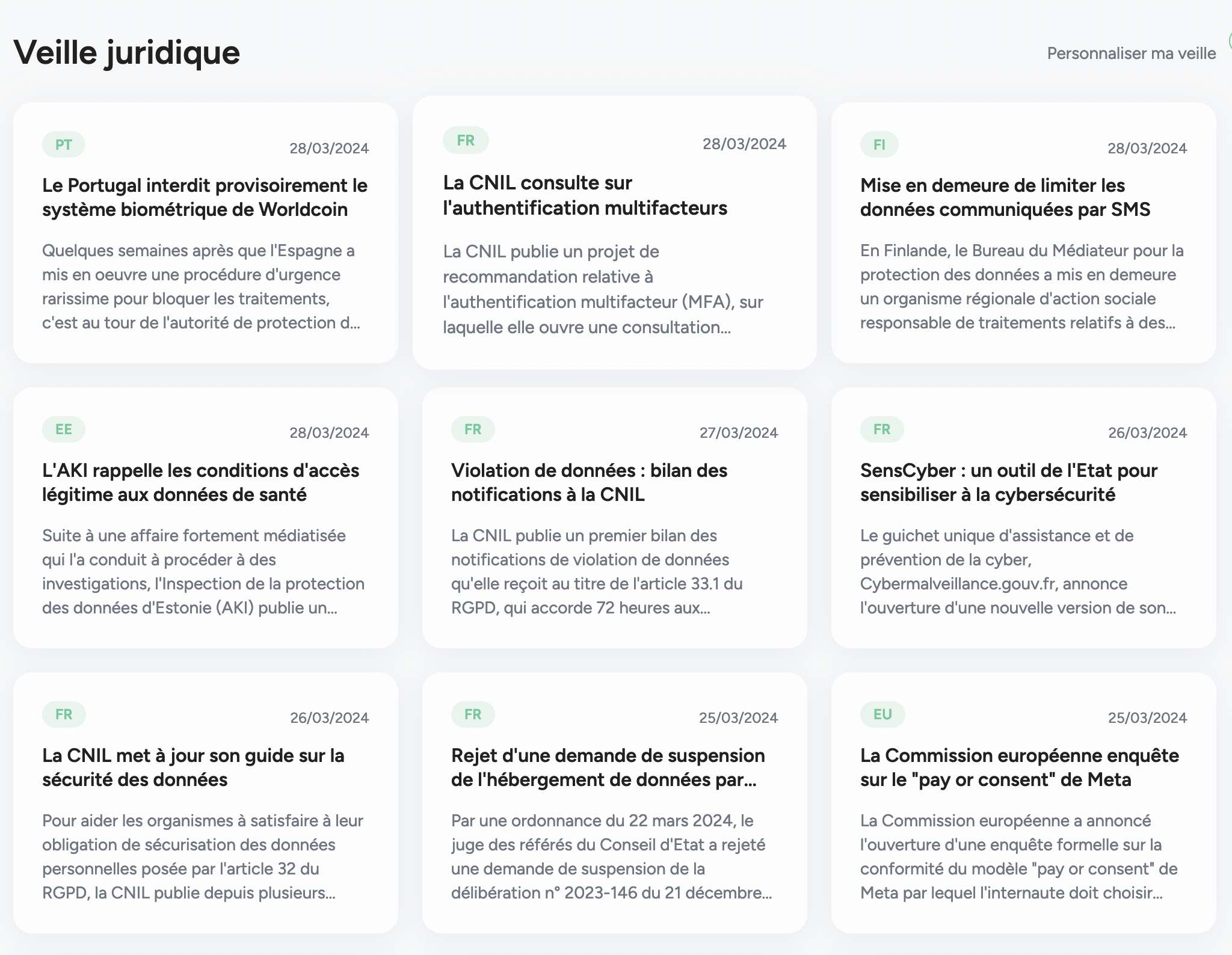

Une veille juridique à la pointe de l’actualité

Rejoignez les 1000+ cabinets et DPOs déjà inscrits

Environ 20 heures

par semaine gagnées

de marge gagnés

DPO & cabinets utilisateurs quotidien

Audit RGPD effectués

Contactez-nous

CGU – Olympe App

Politique de confidentialité – Olympe App

Mentions légales – Olympe App

DPA – Olympe App

CGU – Olympe.legal

Politique de confidentialité – Olympe.legal

Mentions légales – Olympe.legal

Legal Index